John Miers, PhD candidate and Lecturer in Academic Support and BA (Hons)/MA Culture, Criticism and Curation, Central Saint Martins

An emphasis on the embodied and performative aspects of drawing has become a common feature of the way this foundational artistic activity is understood. Yet in both pedagogy and practice this emphasis is often accompanied by a relative inattention to drawing’s depictive and narrative affordances. In July 2016, the UAL / House of Illustration collaboration Markings: Festival of Illustration and Performance sought to highlight the role of depictive and narrative artforms both as and for performance. This paper takes a case study approach, identifying the themes around which the Markings symposium coalesced, arguing for the importance of depictive seeing in generating and communicating knowledge.

illustration; performance; embodiment; depiction; logic; event review

The idea that drawing is a performative act, perhaps even a type of performance in itself, is well-established in contemporary drawing theory. As Birgitta Hosea remarks, ‘the act of drawing is increasingly being seen as the record of a performance, as the aftermath of an action, the trace of the presence of an artist’s body.’ (2010, p.363). Reflecting on the use of drawing in teaching and research at the University of the Arts London (UAL), James Faure Walker observes that contemporary drawing exists in an ‘ “expanded field”, expanded not only in what can be counted in as drawing, but also how we can think about drawing’. As productive as this expansion might be, he goes on to sound a more cautionary note: ‘as the subject expands, much of what previously made up the centre receives less attention: objective drawing, realism, graphic art, become classified under technical skill’ (Walker, 2014, p.75).

Markings: Festival of Illustration and Performance, held at the Kings Cross campus of Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design (UAL) and the nearby House of Illustration on 8 and 9 July 2016, embraced the performative nature of drawing, but also sought to refocus visitors' attention on those aspects which Walker identifies as currently receiving less attention. The festival was convened by Professor Roger Sabin, whose own research has highlighted the interaction between illustrated and performed artforms, perhaps most notably in his discussions of the appearances of nineteenth century British comics character Ally Sloper in music hall theatre (Sabin, 2003). Markings was a truly cross-university event with contributions from London College of Communication (LCC), Chelsea College of Arts, Camberwell College of Arts, Wimbledon College of Arts (CCW) and a wide variety of performances and workshops from staff and students at London College of Fashion (LCF).

This case study focuses on the symposium that took place on Friday 8 July and the drawings that were produced (performed?) in response to the presentations, but it is worth emphasising first that, despite the present focus on drawing, I am not positioning illustration as simply a specific variety of drawing. Even if I were, my position would be undermined by many of the contributions to the festival, as in the Markings on Screen film programme curated by Nilgin Yusuf, or Falling Apart, a sculptural performance by LCF MA Costume Design students Li Xiong, Su Yu Chen, Yung Chi Lin, Xiaolin Jiao and Yi Zhang, which formed the festival finale on 9 July.

The symposium opened with a keynote lecture from Pascal Lefèvre, guest professor at LUCA School of Arts (campus Saint-Lukas Brussels). Lefèvre presented preliminary results from an empirical study of image recognition inspired by a well-known film of Pablo Picasso at work. He sums up his research question as follows:

An intriguing sequence in the French art documentary Le mystère Picasso (Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1955) shows the famous Spanish artist drawing on a blank screen. By continually adding new lines, the various constellations of lines refer to quite different objects: they evolve from flowers over a fish to a rooster, notwithstanding that the earlier representations are still included. What makes our interpretation change over time from one dominant interpretation to another? (Lefèvre, 2016)

To investigate this, Lefèvre devised an evolving drawing, which was shown to spectators under experimental conditions. The spectators were asked to record their interpretation of the drawing at fifteen points in its evolution. The Markings audience were able to examine their own interpretations, as the talk began with a video presentation of that drawing. My own notes from the symposium read: ‘cross, 4, still 4, kite, deffo kite, more kitey, kite with bows, about to crash, condom, snake, snake++, ?? bubbles, ? fish?, corn cob, fish.’

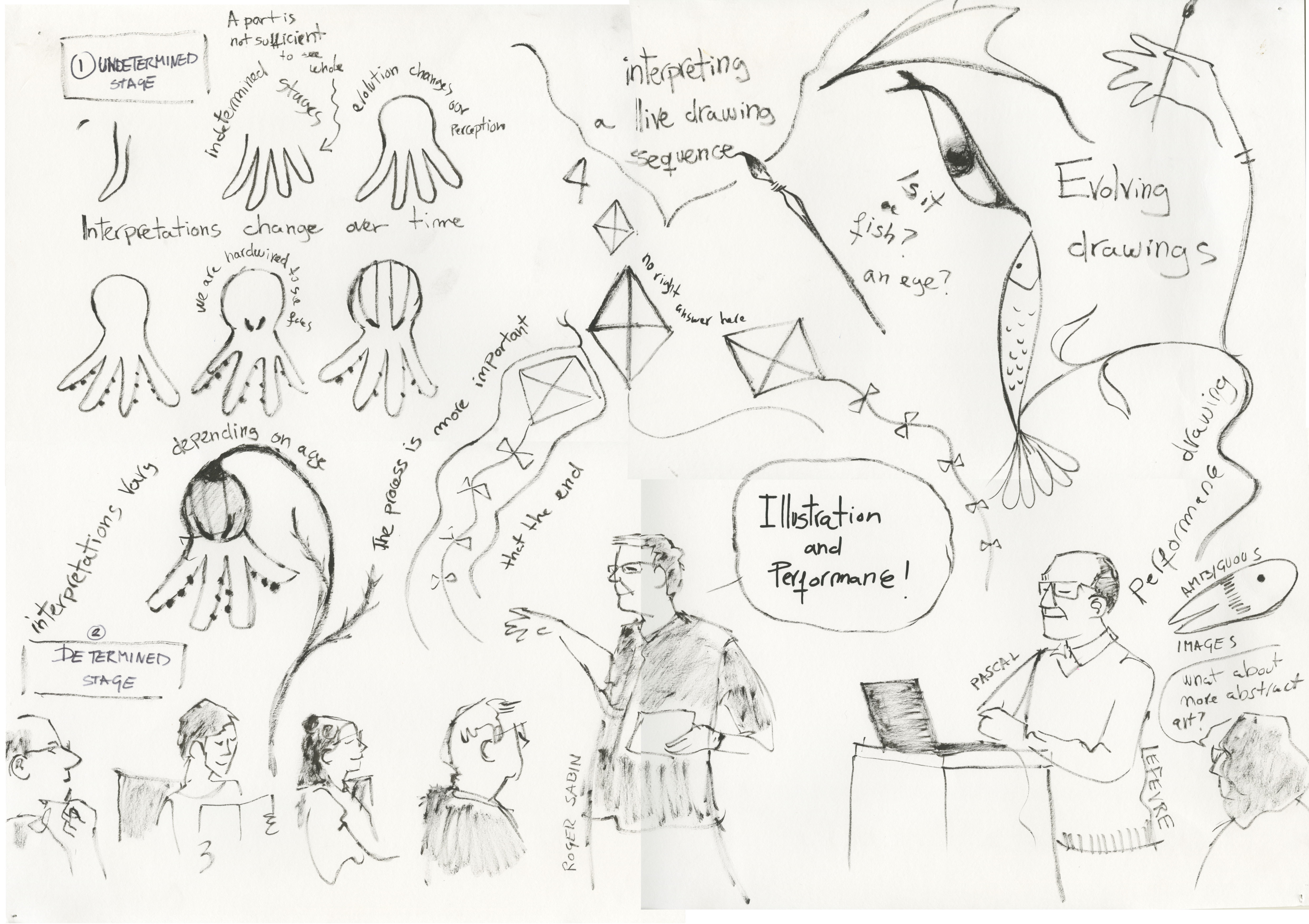

Some of these forms can be seen in the large drawing produced by Aurora Melchor during Lefèvre's lecture (Figure 1). Throughout the symposium, invited artists created drawings in response to the presentations, in full view of the audience. Given the festival's theme, it seemed obvious that illustrations of the ideas being discussed should be captured in drawings that served as both a record of the event and a demonstration of ‘illustration and performance’.

Conceptualising illustrative drawing as performance highlights its operation as an expression of what Robin Nelson calls ‘embodied knowledge’ (2006), a theme that ran through the symposium, linking each contribution. Nelson sees this as distinct from and complementary to the Cartesian method of rational argument that still structures the Western conception of knowledge. He frames it in terms of an artist's ‘training and experience, the “know-how” to make work’ (Nelson, 2006, p.113) and cites theatrical producer Mike Pearson and archaeologist Michael Shanks to argue that ‘the social [also] needs to be understood as an embodied field: society is felt, enjoyed and suffered, as well as rationally thought.’ (Pearson and Shanks, 2001, p.xvi, quoted in Nelson, 2006, p.110).

We see a fluent combination of these forms of knowledge in Melchor's drawing. The bottom row of images depicts audience members and speakers, situating the production of knowledge in a specific social moment. The drawings and text in the top-middle and top-right record key themes and images from the lecture. On the left-hand side, we see a utilisation of her ‘know-how’ in the improvisation of a new set of ambiguous images, invented during the lecture rather than recorded from Lefèvre's slides.

The role of image production and interpretation in generating knowledge emerged as a key theme in Lefèvre's lecture. He concluded that the results of his experiment demonstrated the way in which we form concepts by merging our existing patterns of thought with the sensory stimuli we receive. This was placed in the context of work by psychologists Gerald Long and Thomas Toppino, who identified two key properties of the kinds of forms seen in Figure 1: ambiguity, which refers to ‘the observer’s ability to access multiple representations from the single stimulus pattern,’ and reversibility, ‘the observer’s phenomenal experience of oscillation between those representations’ (2004, p.748). These properties are ‘influenced in varying degrees both by relatively low-level sensory processes that affect perception in a bottom-up manner and by higher order cognitive processes that affect experience in a top-down fashion’ (Long and Toppino, 2004, p.765). Thus, even at the basic level of ‘saying what it looks like’, interpreting an image is no mere matter of naming; rather, like any act of reasoning, it involves the testing of (top-down) hypotheses against the evidence provided by (bottom-up) empirical data.

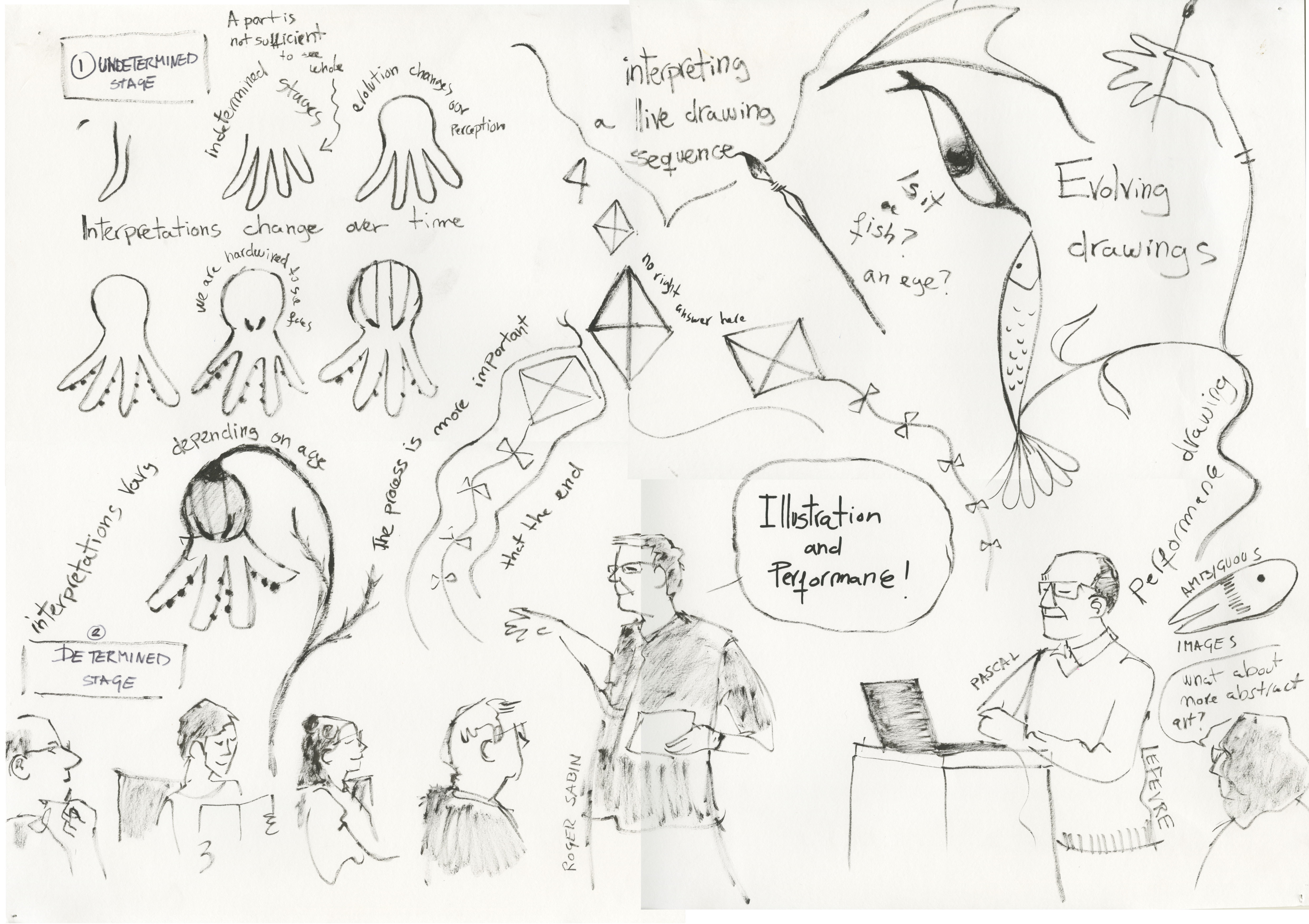

The exploratory and speculative nature of picture-recognition was also highlighted in Tullio Viola's (Humboldt University, Berlin) presentation, which extended the historical context of the keynote by focusing on a drawing performed by philosopher Charles S. Peirce during a lecture given at Harvard University in 1903, versions of which can be seen in the centre and top-right of Melchor’s drawing of this presentation (Figure 2).

In one of his manuscripts Peirce remarked, ‘I do not think I ever reflect in words. I employ visual diagrams, firstly, because this way of thinking is my natural language of self-communion, and secondly, because I am convinced that it is the best system for the purpose.’ (MS 620, quoted in Pietarinen, 2014, p. 117). His use of live-drawing in this 1903 lecture reflects the central place visual perception had in his philosophy. Peirce’s manuscripts record the commentary he gave while making his drawing in front of his audience:

I will show you a figure which I remember my father drawing in one of his lectures […] It consists of a serpentine line. But when it is completely drawn, it appears to be a stone wall. The point is that there are two ways of conceiving the matter. Both, I beg you to remark, are general ways of classing the line, general classes under which the line is subsumed. But the very detailed preference of our perception for one mode of classing the percept shows that this classification is contained in the perceptual judgement.

(Peirce, EP 2: 228, quoted in Viola, 2012, p.121-122 ‐ emphasis added).

As Viola emphasised in his discussion of Peirce’s experiment, making sense of what we see is a fundamental cognitive activity that is not conducted post-hoc: knowing is contained in seeing. Peirce saw the type of perceptual judgement involved in classifying an ambiguous shape ‐ such as his serpentine line / stone wall drawing ‐ as characteristic of a type of logic he called abduction. In Peirce's system there are three distinct types of inferential process involved in reasoning: deduction, induction, and abduction. Deduction is drawing logical conclusions from premises, as in the basic syllogism ‘All As are Bs. C is a B. Therefore, C is an A’. Being based wholly on already established principles, deduction cannot lead to new knowledge (Yu, 1994, p.13). Induction involves drawing probable conclusions from instances: if we have observed 100 As and found them all to be Bs, it is probable that all As are Bs. Such a proposition is a little more speculative than that found by deduction, but it still rests on prior knowledge: how do we decide that the 100 As we have observed are actually Bs? This has to involve abduction, which ‘is the perception of possible interconnectedness of thoughts’ (Houser, Roberts and Evra, 1997, p.473) and, in Peirce's own words, is ‘the only logical operation which introduces any new idea’ (Minnameier, 2010, p.240). Therefore in this framework, the drawings produced during the Markings seminar ‐ and indeed any process of exploratory drawing ‐ do not simply record ideas, but constitute a powerful method of understanding and extending those ideas. As in Nelson's notion of embodied knowledge, our physical engagement with the world is necessary for thinking to occur. Viola concluded his talk by quoting Peirce once more: although the unaided, logical mind is limited to working only with what has already been presented to it, ‘the mind working with a pencil and plenty of paper has no such limitations.’ (Peirce, 1887, p.169).

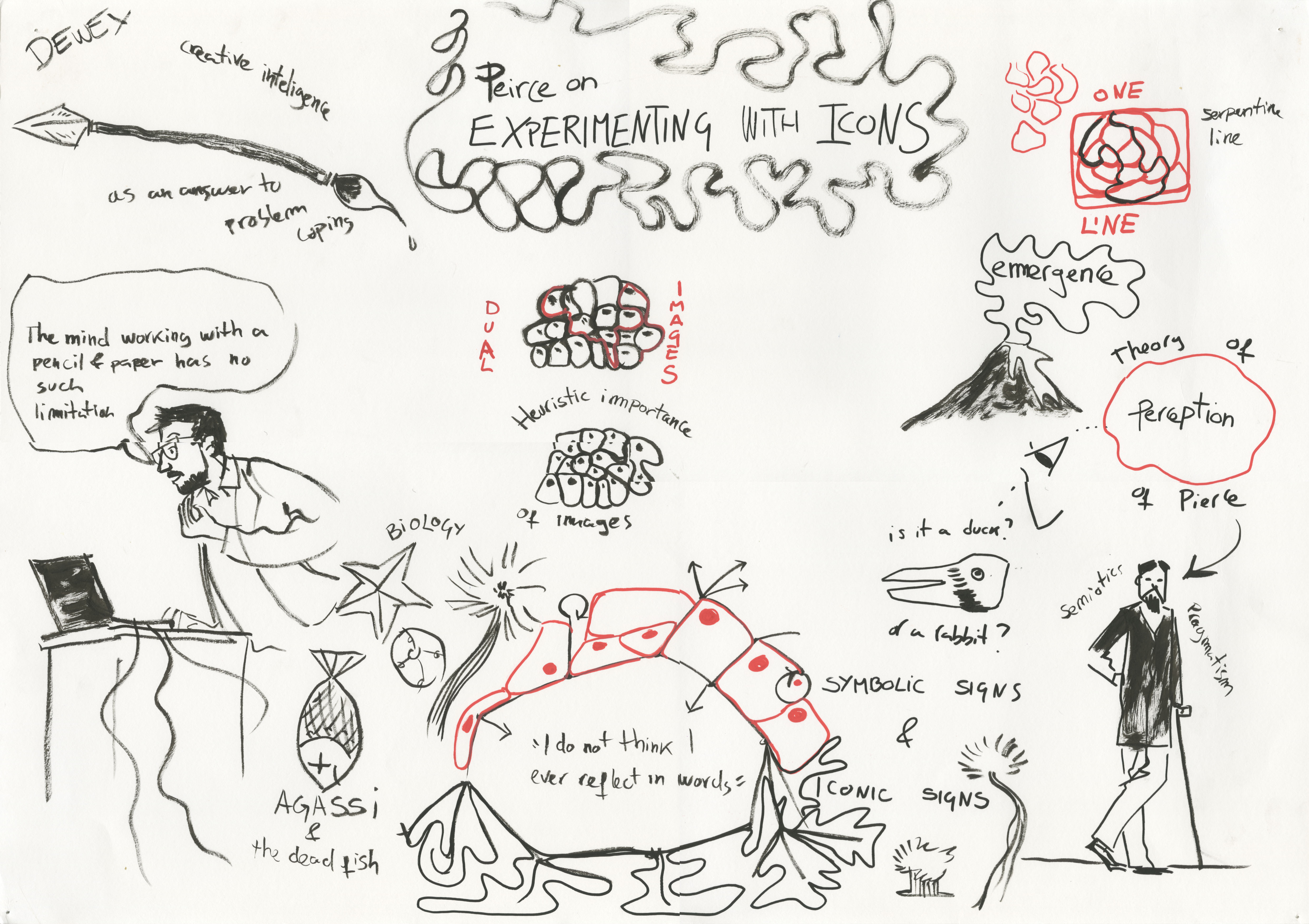

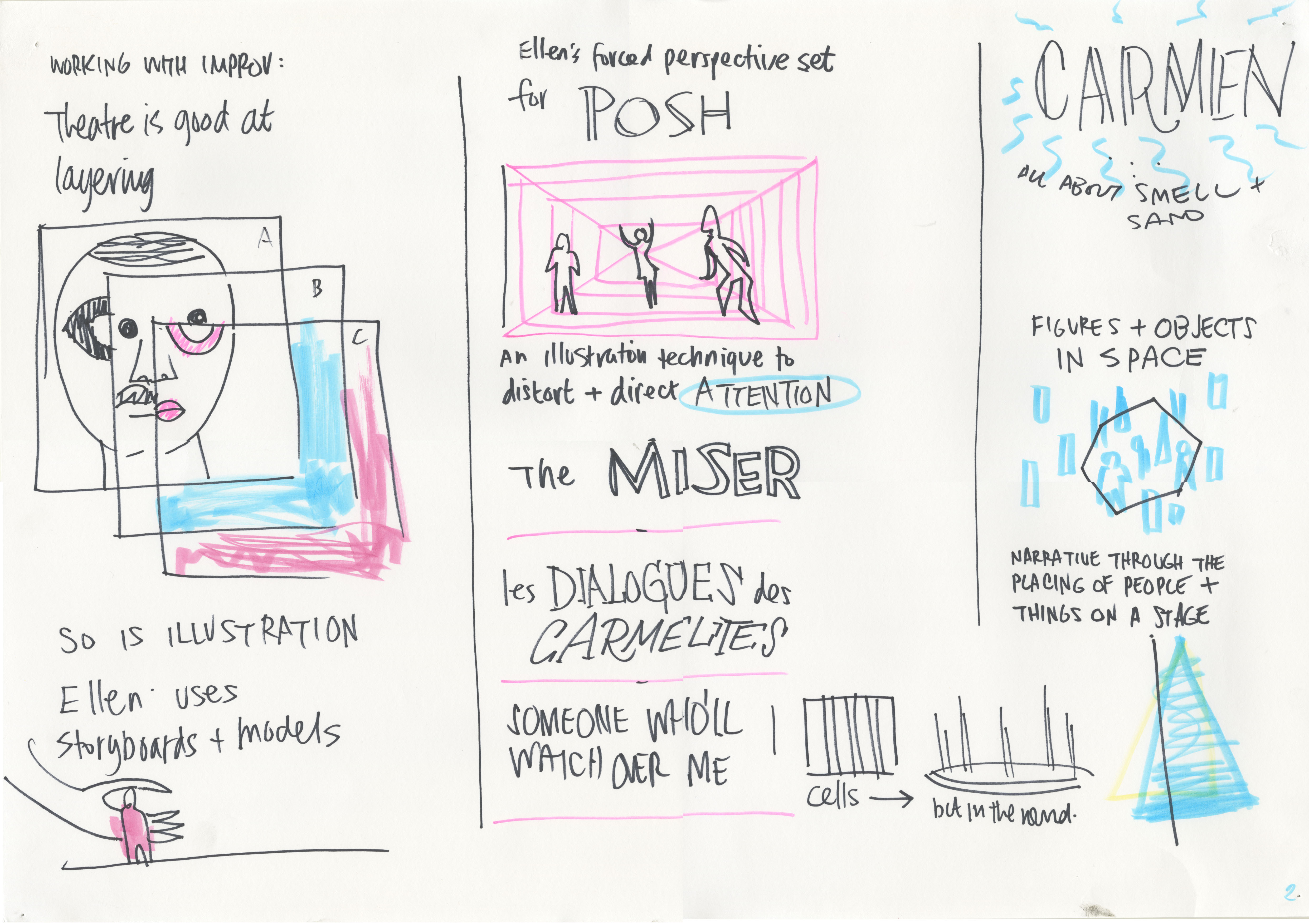

The next two presentations focused on examples of practices that blend illustration with performance. Illustrator Viv Schwarz and scenographer Ellan Parry spoke about their individual work and their collaborative masterclass The Theatre of Illustration. This project posed the question ‘What is a picture book if not a tiny paper theatre?’ (Schwarz, 2015), aiming to ‘entice [author-illustrators] away from their desks and introduce them to a practical, physical and participatory experience of scenographic and theatrical processes, which could then be carried over into their illustration practice.’ (Schwarz and Parry, 2016). Embodied knowledge once again emerged as a key theme, as seen in the summary of their conclusion in the drawing performed by cartoonist and graphic designer Woodrow Phoenix: ‘Improv ties Viv and Ell[a]n's practise together […] understand who the characters are by inhabiting them’ (Figure 3).

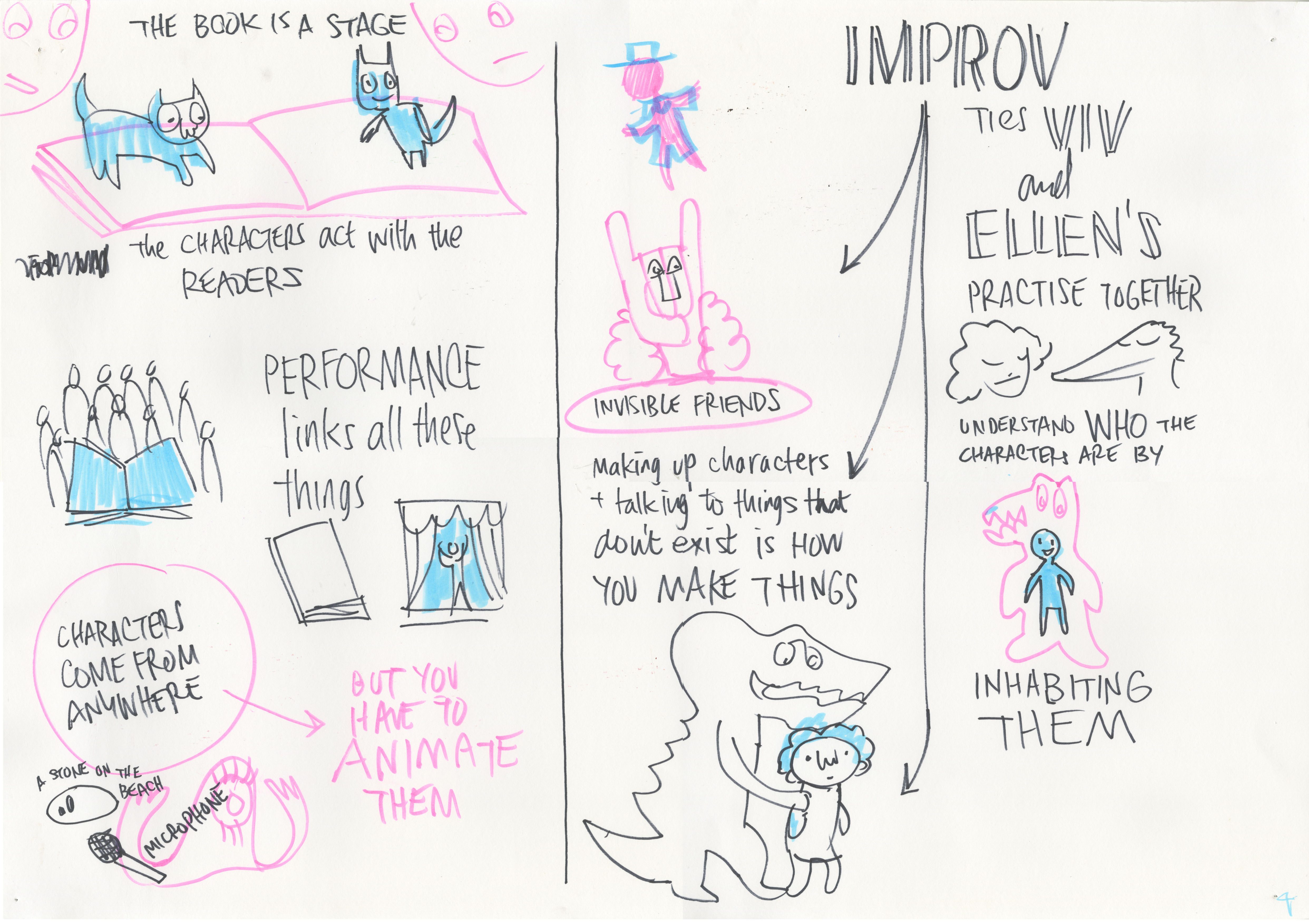

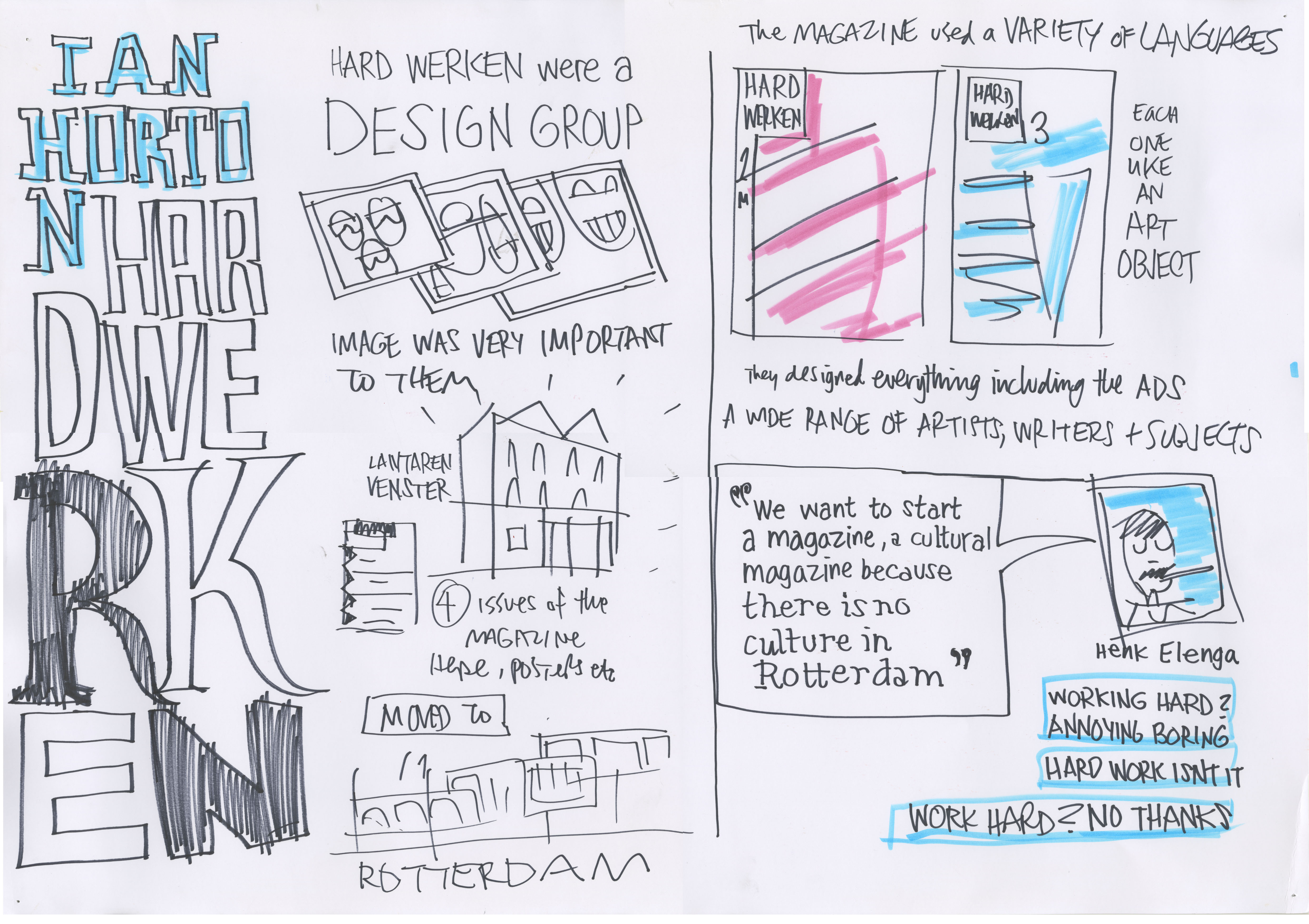

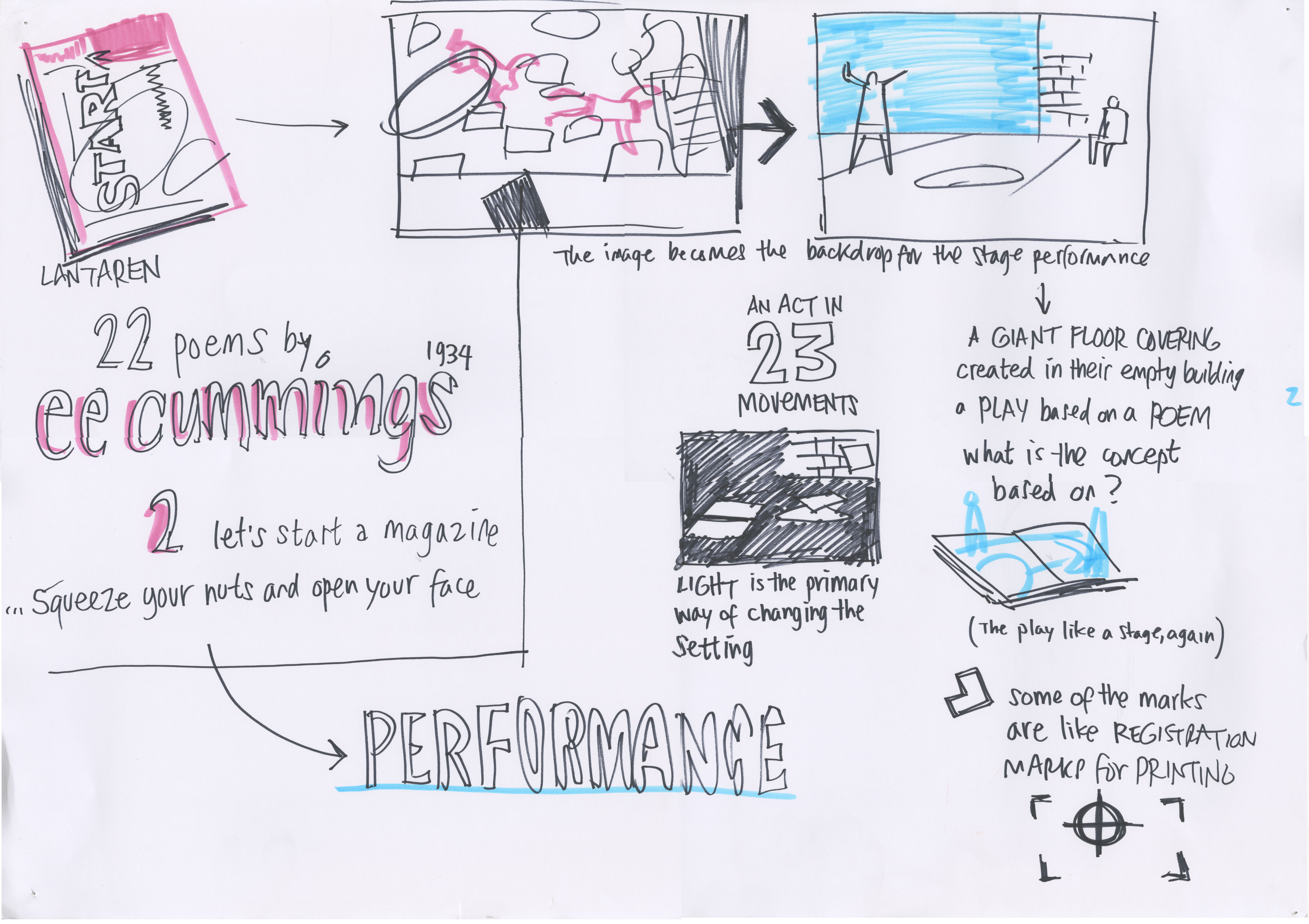

Phoenix's drawings demonstrate a different mode of visual reasoning. Rather than create a holistic, all-at-once record of both the presentation and the experience of hearing it, as in Melchor's work, he produced multiple drawings, translating key points into concise graphic symbols. Using Peirceian terminology, we might say that he abducted what he was seeing and hearing, as in his repurposing of the notion of ‘layering’ in Figure 4.

Ian Horton (LCC) presented a fascinating example of a performance that brought together magazine design, illustration, poetry and theatre, examining ‘the relationship between the graphic staging of the performance Let’s Start a Magazine and the visual style of the cultural magazine Hard Werken, both produced in Rotterdam in the early 1980s’ (Horton, 2016). Phonenix's graphic interpretations (Figures 5 and 6) both tell the story and embody the cross-fertilisation of ideas involved in this project:

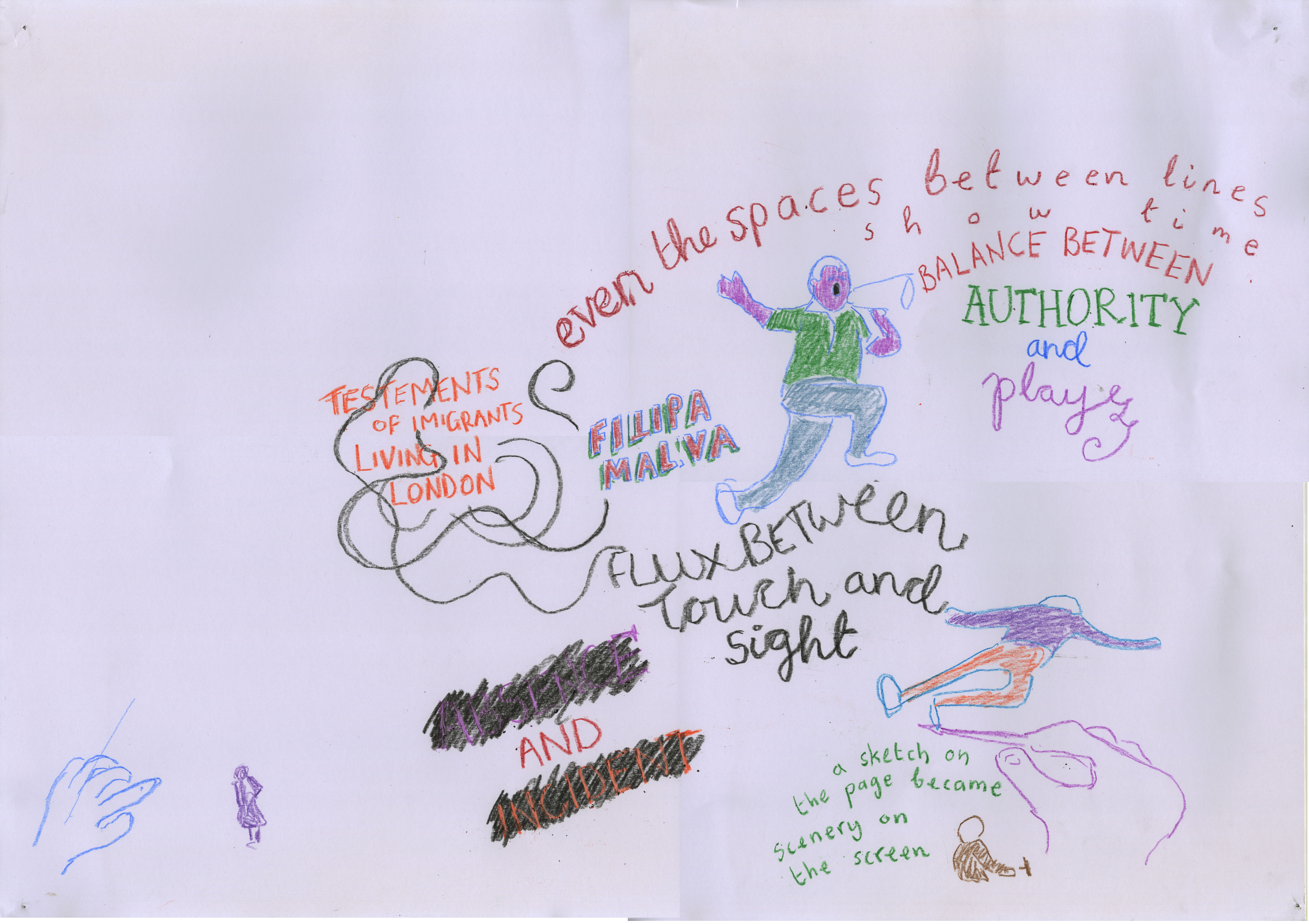

The next section of the symposium saw shorter papers from four artists who were either working on, or had recently completed, PhD research. The themes established by the first set of presentations were re-examined and enacted through this series of talks. Scenographer and drawing practitioner Filipa Malva spoke about her use of drawing in the development and performance of O Meu País é o Que o Mar Não Quer (My Country is What the Sea Does not Want, directed by Ricardo Correia, Casa da Esquina, Coimbra). Drawing was used not only to design props and scenery, it was also used in rehearsal, setting up a reciprocity between the gestures that produce drawn marks and the gestures of the performer. Malva described the way in which her drawings enabled actors to reframe their physical presence on the stage. In this sense her practice extends Hosea’s reflection on the understanding of drawing given in the introduction to the symposium: drawing is not just an aftermath of action, it becomes a provocation to further action.

This set of papers was interpreted by graphic novelist Gareth Brookes, who used wax crayons rather than markers. Rougher in texture and more sensitive to variations in pressure, this medium emphasises drawing's tactility, or as Malva put it, ‘the symbiosis between touch and sight which comes naturally to a drawer’ (2016).

In Figure 7 Brookes emphasises his own presence at the drawing board (or perhaps his imagining of Malva's presence at her drawing board) by the inclusion of two hands at the bottom corners, the right of which is holding a stylus. Looking at this drawing, we have a sense of the marks arriving in the moment of insight that, for Peirce, is characteristic of abduction. Patrick Maynard says of the experience of looking at rapidly-executed drawings by cartoonists that ‘we seem to see the visage taking form, being drawn ‐ and it is fairly common that this will appear to have been done swiftly and with very few marks […] [the marks seem] like flights of birds that have settled here but may suddenly go off in another pattern and direction’ (2005, p.198 ‐ emphasis by Maynard). Drawing does not just present knowledge or a record of experience, but invites the viewer to share in it by re-enacting the impulse they see fixed in ink, charcoal or wax.

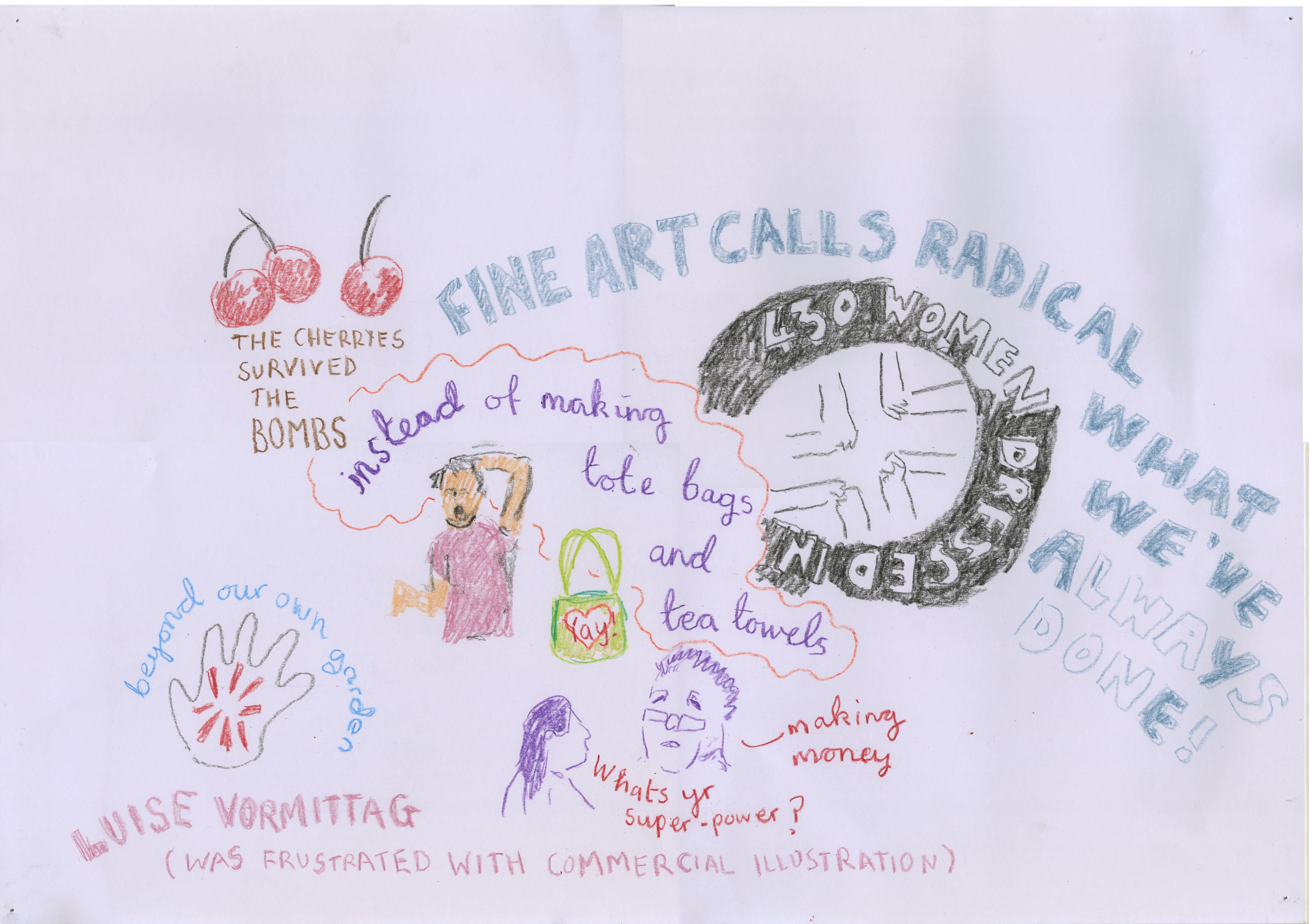

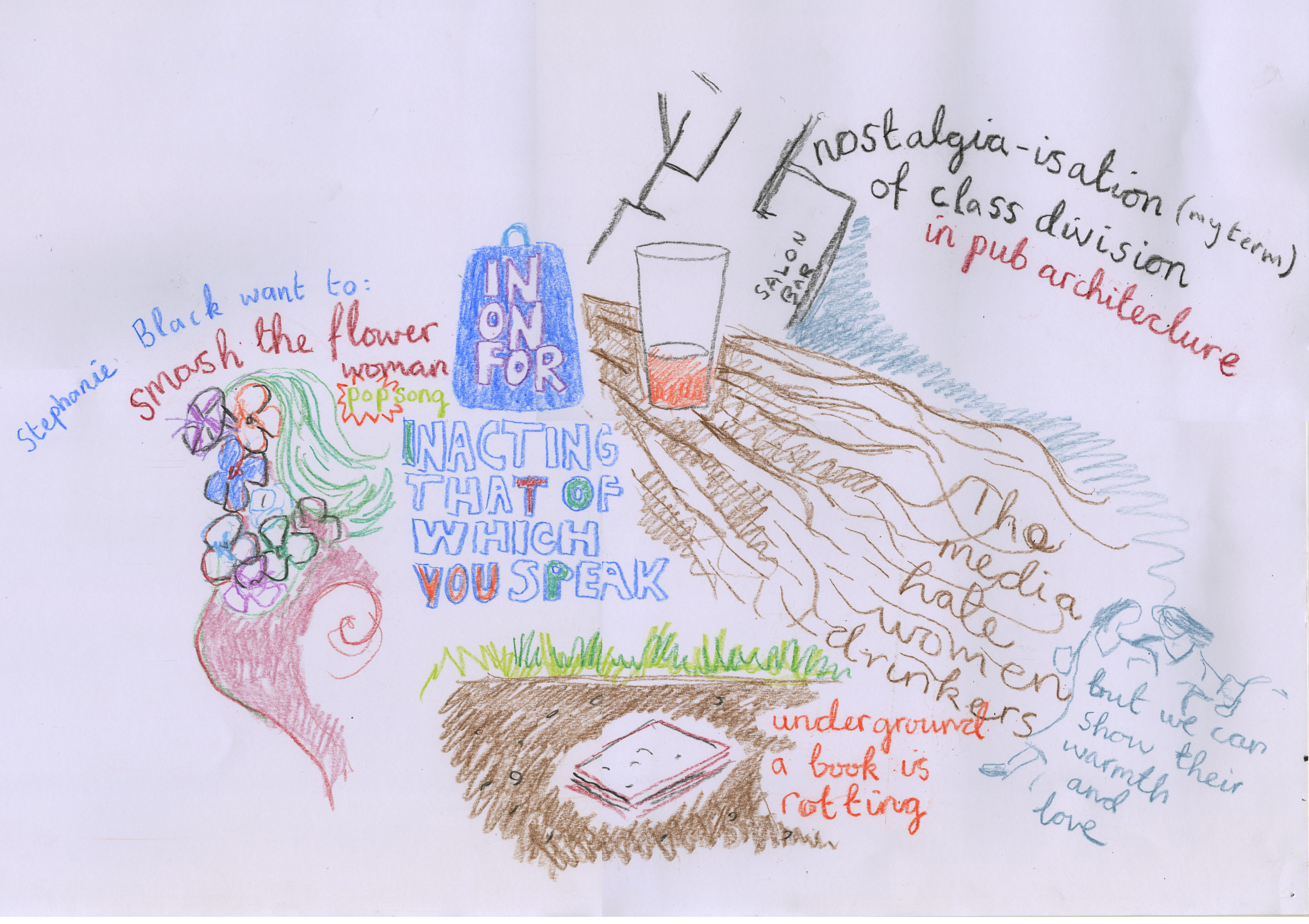

Brookes' drawings occupy something of a middle-ground between the approaches taken by Phoenix and Melchor. Like Phoenix, his focus is on recording the content of the talks; with the exception of the hands in Figure 7, none of the pictorial forms refer directly to the physical environment in which they were made. But rather than digesting the ideas presented in these images sequentially, as we do with Phoenix's work, they are encountered holistically, ‘all-at-once’, as in Melchor's work. Figures 8 and 9 interpret talks by Luise Vormittag (CSM and LCC) and Stephanie Black (University of the West of England), both of whom challenged established notions of what illustration is and how it is received. Vormittag placed her practice in a context of social engagement and collaboration, with reference to her participatory installation project The Most Powerful Cabinet in Whitechapel (2014). Black also emphasised approaches to illustration that move beyond ‘industry-oriented, brief-led ways of working’ (2014, p.27), echoing the symposium's emergent focus on drawing as a means of enacting understanding by arguing that illustrator-researchers should embrace the use of text/image relationships as means of expanding the ways and contexts in which research outcomes can be communicated.

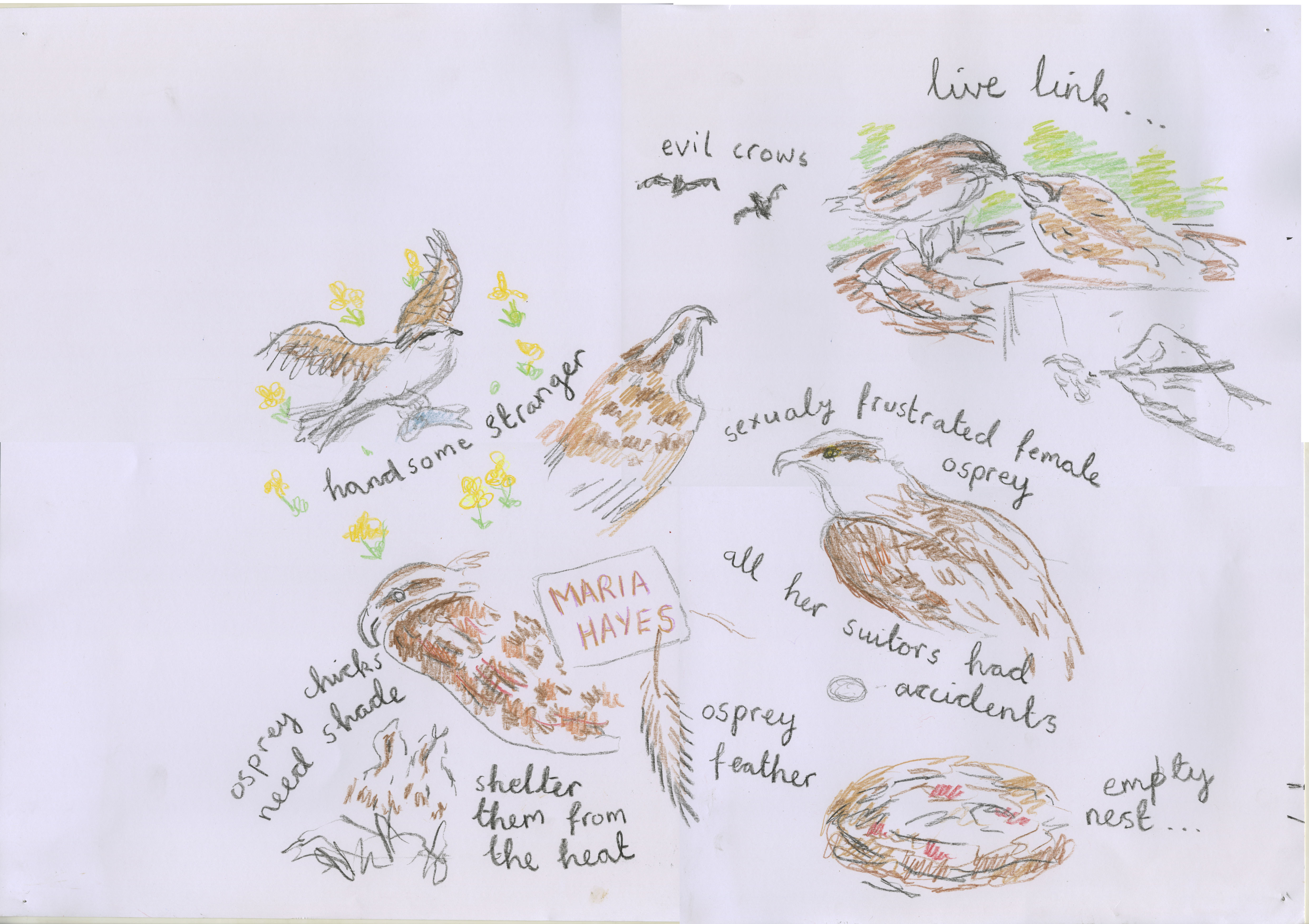

The final two presentations were conducted as performances. Camilla Brueton (CCW) performed her essay Framing the City, in which collages and fragments of text combined to create a series of reflections drifting through the urban landscape, a Situationist dérive anchored by imagery. Maria Hayes (Aberystwyth University) described her work as artist-in-residence at the Glaslyn Osprey centre, using her drawings to narrate the tale of The Seventh Egg. She concluded by showing a live video feed of the ospreys, inviting the audience to draw with her, an opportunity which, as we see in Figure 10, Brookes embraced.

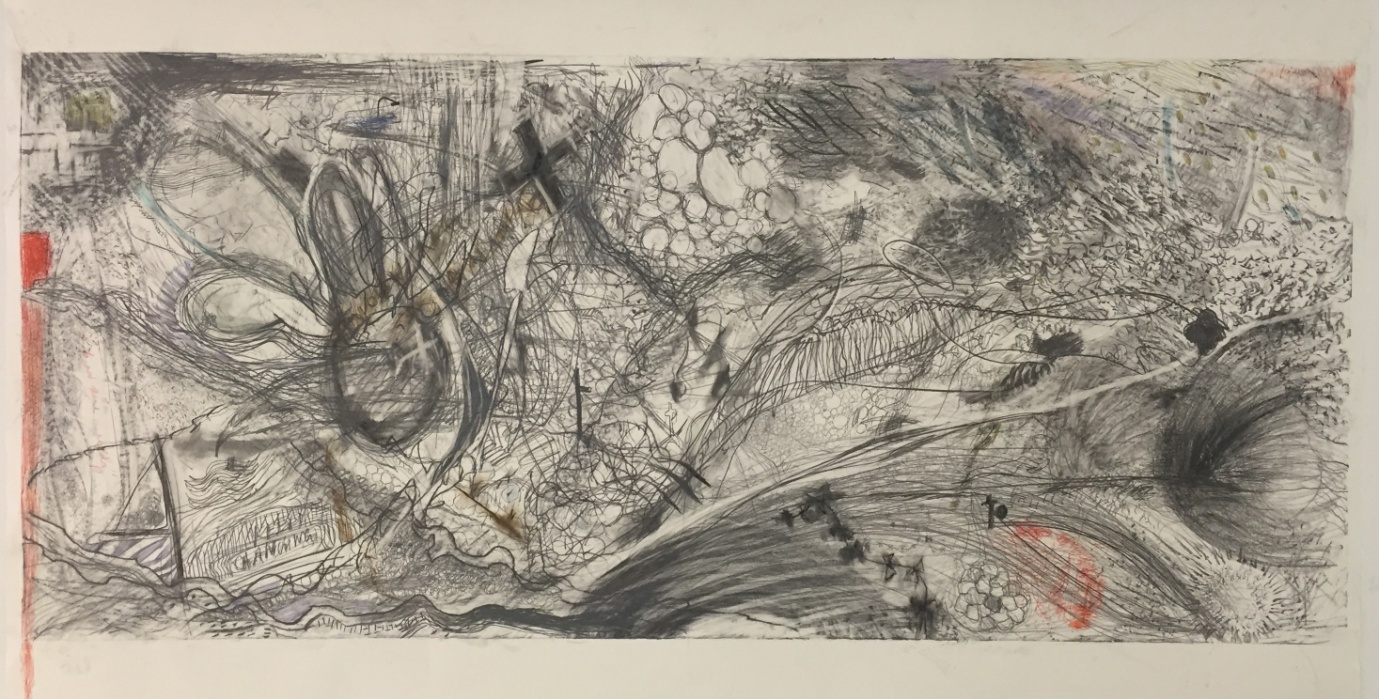

That was the end of the symposium, but not the end of the drawings it generated. Towards the end of the symposium, Hayes reminded the audience that drawing can be a communal activity. This communality was reinforced when the festival moved from House of Illustration to CSM's Lethaby Gallery. Figure 11 shows the large-scale charcoal drawing produced by the performance drawing group Drawn Together (Birgitta Hosea, Carali McCall, Jane Grisewood, Maryclare Foa) as part of the evening performance programme. All four Drawn Together artists sat around a table and drew simultaneously on this 2000x1000mm paper, discussing the day's presentations, with microphones amplifying their conversations and the scrape of charcoal. Close inspection reveals traces of Peirce's serpentine line and Lefèvre's evolving drawing.

Birgitta Hosea concludes the article quoted in the introduction to this review by discussing her collaborative practice as a member of Drawn Together. She explicitly places their work within the kind of historical context explored by Roger Sabin:

Our experimentation with the process of live drawing is created as a performance in front of a live audience, reminiscent of the chalk talks or lightning sketch act performed in the Victorian vaudeville or music halls by artists such as Walter Booth or J. Stuart Blackton. (Hosea, 2010, p.364)

Artists and performers were using live illustration in popular entertainments during the same years that Peirce was developing his use of live illustration as a tool for philosophical investigation. Cartoonist and chalk talk performer John Wilson Bengough echoed Peirce’s argument that the classification of percepts serves as a model for logical inferences of all kinds when he remarked at the beginning of a performance:

I will endeavour to demonstrate that in almost every department of thought and study there is an element of the pictorial; that suggestions for pictures are to be found practically everywhere, if you only have the eye to see them. Of course, this is the eye of the imagination, which is the organ of the faculty of observation.

(Bengough, 1922, pp. 40-41)

Philosopher and cartoonist both invited their audiences to use the live production of an illustration as a spur to further imaginative exploration of the world. The Markings symposium suggested that the traditions represented by these individuals were never really that far apart.

Bengough, J.W. (1922) Bengough’s chalk-talks. Toronto: The Musson Book Company. Available at: https://archive.org/download/bengoughschalkta00benguoft/bengoughschalkta00benguoft.pdf (Accessed 9 December 2016)

Black, S. (2014) ‘Illumination through illustration: research methods and authorial practice’, Journal of Illustration, 1(2), pp. 275‐300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1386/jill.1.2.275_1.

Black, S. (2016) ‘Plume of feathers: performativity and performance’, Markings Illustration and Performance Festival, Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design (UAL) and House of Illustration, 8‐9 July. Available at: https://markingsual.co.uk/plume-of-feathers-performativity-and-performance/ (Accessed: 9 December 2016).

Hayes, M. (2016) ‘The seventh egg’, Markings Illustration and Performance Festival, Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design (UAL) and House of Illustration, 8‐9 July. Available at: https://markingsual.co.uk/hayes/ (Accessed: 9 December 2016).

Horton, I. (2016) ‘Let’s start a magazine (a Hard Werken production)’, Markings Illustration and Performance Festival, Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design (UAL) and House of Illustration, 8‐9 July. Available at: https://markingsual.co.uk/horton/ (Accessed: 28 September 2016).

Hosea, B. (2010) ‘Drawing Animation’, Animation, 5(3), pp. 353‐367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1746847710386429.

Houser, N., Roberts, D. D. and Evra, J. V. (eds.) (1997) Studies in the Logic of Charles Sanders Peirce. Indiana University Press.

Lefèvre, P. (2016) ‘Evolving drawings and their changing interpretation’, Markings Illustration and Performance Festival. Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design (UAL) and House of Illustration, 8‐9 July. Available at: https://markingsual.co.uk/lefevre/ (Accessed: 28 September 2016).

Long, G. M. and Toppino, T. C. (2004) ‘Enduring interest in perceptual ambiguity: alternating views of reversible figures’, Psychological Bulletin, 130(5), pp. 748‐768. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.748.

Malva, F. (2016) ‘Of lines, zoom and focus: mediating drawing in performance’, Markings Illustration and Performance Festival, Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design (UAL) and House of Illustration, 8‐9 July. Available at: https://markingsual.co.uk/malva/ (Accessed: 28 September 2016).

Maynard, P. (2005) Drawing distinctions: the varieties of graphic expression. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Minnameier, G. (2010) ‘The logicality of abduction, deduction, and induction’, in Bergman, M., Paavola, S., Pietarinen, A-V. and Rydenfelt, H. (eds.) Ideas in action: proceedings of the Applying Peirce Conference. Helsinki: Nordic Pragmatism Network, pp. 239‐251. Available at: http://www.nordprag.org/nsp/1/Minnameier.pdf (Accessed: 28 September 2016).

Nelson, R. (2006) ‘Practice-as-research and the problem of knowledge’, Performance Research: Av Journal of Performing Arts, 11(4), pp. 105‐116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13528160701363556.

Peirce, C. S. (1887) ‘Review of Logical Machines’, The American Journal of Psychology, 1(1), pp. 165‐170. Available from: www.jstor.org/stable/80000263 (Accessed: 14 November 2016).

Pietarinen, A-V. (2014) ‘Diagrams or rubbish’, in Thellefsen, T., and Sorensen, B. (eds.) Charles Sanders Peirce in his own words: 100 years of semiotics, communication and cognition. Boston / Berlin: Walter de Gruyter

Sabin, R. (2003) ‘Ally Sloper: the first comics superstar?’, Image and Narrative, (7). Available at: http://www.imageandnarrative.be/inarchive/graphicnovel/rogersabin.htm (Accessed: 28 September 2016).

Schwarz, V. (2015) ‘The theatre of illustration’, Letters from Schwartzville, 17 October. Available at: http://vivianeschwarz.blogspot.com/2015/10/the-theatre-of-illustration.html (Accessed: 28 September 2016).

Schwarz, V. and Parry, E. (2016) ‘The theatre of illustration’, Markings Illustration and Performance Festival, Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design (UAL) and House of Illustration, 8‐9 July. Available at: https://markingsual.co.uk/viv-schwarz-and-ellan-parry-the-theatre-of-illustration/ (Accessed: 28 September 2016).

University of the Arts London (UAL) and House of Illustration (2016) ‘Markings symposium programme’, Markings: Illustration and Performance Festival, 8‐9 July. Available at: https://markingsualcouk.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/markingssymposiumprogramme_web.pdf (Accessed: 15 November 2016).

Viola, T. (2012) 'Pragmatism, bistable images, and the serpentine line: a chapter in the prehistory of the Duck-Rabbit', in Engel, F., Queisner, M. and Viola, T. Das bildnerische Denken: Charles S. Peirce. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 115‐138.

Viola, T. (2016) ‘Peirce on experimenting with icons’, Markings Illustration and Performance Festival, Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design (UAL) and House of Illustration, 8‐9 July. Available at: https://markingsual.co.uk/viola/ (Accessed: 15 November 2016).

Vormittag, L. (2014) ‘Making (the) subject matter: illustration as interactive, collaborative practice’, Journal of Illustration, 1(1), pp. 41‐67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1386/jill.1.1.41_1.

Vormittag, L. (2016) ‘Making (the) subject matter: illustration as interactive, collaborative practice’, Markings Illustration and Performance Festival, Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design (UAL) and House of Illustration, 8‐9 July. Available at: https://markingsual.co.uk/vormittag/ (Accessed: 15 November 2016).

Walker, J. F. (2014) 'Learning to draw from forgotten manuals', in Almeida, P. L., Duarte, M. D. and Barbosa, J. T. (eds.) Drawing in the University Today. Porto: i2ADS, pp. 73‐80.

Yu, C. H. (1994) ‘Abduction? Deduction? Induction? Is there a logic of exploratory data analysis?’, Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans/LA, 4‐8 April. Available at: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED376173 (Accessed: 28 September 2016).

John Miers is a cartoonist and researcher currently working on a practice-based PhD at Central Saint Martins exploring the use of visual metaphor in comics and graphic novels. At CSM he is a tutor and lecturer for the Culture, Criticism and Curation programme and for their Academic Support provision; he also works as a critical and historical studies lecturer for BA Illustration/Animation at Kingston University.